News

College of Charleston Researcher Uses New Fossils to Learn More About the Evolution of Baleen Whales

Some recently discovered fossils are helping College of Charleston research associate Robert Boessenecker answer questions surrounding the evolution of early toothed baleen whales. The research, recently published in the journal PeerJ, offers a better understanding of the early growth and development of these whales, which lived along the South Carolina coast about 30 million years ago.

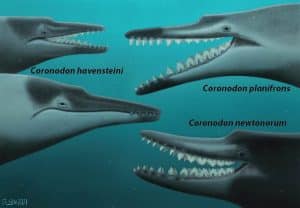

Several years ago, a wealth of new fossils of the early toothed baleen whale Coronodon were discovered within Oligocene (23–30 million years old) rock layers near Charleston. The fossils, nearly all of which were found and donated by amateur fossil collectors, included five new skulls representing two new species: Coronodon planifrons and Coronodon newtonorum, and young juveniles of Coronodon havensteini. Coronodon is one of the most primitive members of the group that includes living baleen whales – its name translates to “crown tooth,” referring to the large, multi-cusped teeth that overlap in the mouth. The scientific community continues to debate whether these teeth were used for cutting, filter feeding, or a combination of both.

The different specimens, which belong to the College’s Mace Brown Museum of Natural History as well as the Charleston Museum, helped Boessenecker, who co-authored the research with Jonathan H Geisler and Brian L Beatty of the New York Institute of Technology, begin to connect the dots between the various Coronodon species and today’s living baleen whales.

“This study shows that these whales diversified here along our coast shortly before going extinct, and our large sample of skulls and skeletons of Coronodon is an important window into their growth, species variation and life habits,” says Boessenecker.

The two new species, Coronodon planifrons and Coronodon newtonorum, were found in the same rock layer and date to the same time period (late Oligocene; 23–25 million years old). Coronodon havensteini (28–30 million years old) is older and is a possible ancestor of these two species. Coronodon planifrons is named after a skull with a flat forehead and possibly an extra toothed relative of the other species. Coronodon newtonorum is also known for a single skull and mandible, with slightly smaller teeth and an unusual shaped mouth that made it look like it was permanently smiling.

The new specimens of Coronodon havensteini include an old adult and two calves and provide new insight into the early growth and development of Oligocene whales. Unlike modern dolphins and baleen whales, the snout stays the same length during growth – rather than being shorter in juveniles. The early growth of the snout is probably related to its large teeth, and underscores how important the teeth are to understanding this early whale.

These new specimens and species indicate that Coronodon had a proportionally large head relative to its skeleton, swam in a style much like modern baleen whales, and likely had a flexible chin and joints in the skull that are typically associated with filter feeding. However, Coronodon, appears to have lacked baleen. Reconstruction of the evolutionary tree of baleen whales places Coronodon as its earliest branch and is key to understanding the transition from feeding with teeth to feeding with baleen.

“There are almost no other species of early baleen whales for which we have more than a single specimen,” says Boessenecker, who is also an adjunct instructor in the College’s Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences. “We now know what happened to the shape of the skull and eruption and wear of the teeth during the lifespan of Coronodon – something we knew nothing about for any other toothed baleen whales.”